The Southern African region had in the past few years experienced an improvement in the media freedom environment.

However, the last year has been characterised by democratic backsliding that has manifested in growing impunity for crimes against journalists and weaponisation of the law against the media.

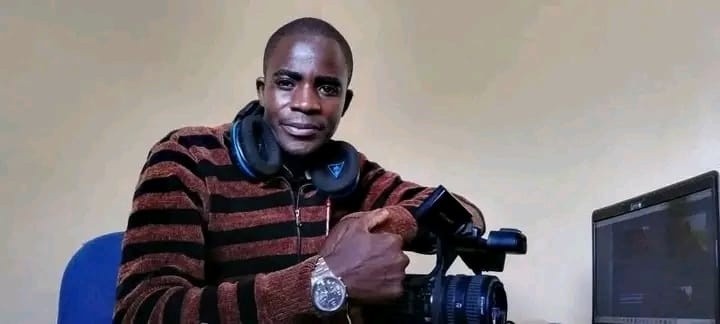

The killing of the Lesotho broadcaster, Ralikonelo “Leqhashasha” Joki, in May this year as he left his workplace, remains a scar on the conscience of the Southern African region. The pace to get justice for the slain broadcaster is painstakingly slow.

Such developments only serve to embolden perpetrators of crimes against journalists.

This comes against the background of the disappearance of Azory Gwanda in Tanzania and the murder of Blandina Sembu, a presenter with Tanzania’s ITV and Radio One.

The Mozambique journalist Ibrahimo Mbaruco remains unaccounted for more than three years after he went missing.

We cannot tire in demanding justice and accountability for these journalists and many others before them.

While murders and disappearances are the extreme form of attacks, violence against journalists has become more subtle and, in some cases, legalised.

Cybersecurity laws, which promote surveillance and discourage whistleblowing have become the norm. Strategic lawsuits against public participation are also some of the new ways that state and non-state actors are targeting the media fraternity.

This is coupled with non-governmental organisations legislation that limits freedom of expression and association. There has been a proliferation of such laws in the Southern African region.

In addition, the ubiquity of the internet and social media has translated into the growth of online attacks against journalists, with the particular targeting of female journalists.

As we commemorate this year’s International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists, we remind countries in the region that they have a duty to comply with their positive obligations to prevent, protect and provide justice.

In terms of the duty to prevent crimes against journalists, governments in the region need to adopt a discourse that contributes to preventing violence against journalists and refrain from inflammatory statements that increase the risk inherent in their work.

This means public officials should be clear and consistent in affirming the rights of journalists to operate freely, even if their work may sometimes be critical of public authorities.

The duty to prevent attacks on journalists is particularly more pronounced during electoral periods. The next two years are a busy period for Southern Africa, as a number of countries are due to hold elections.

Electoral periods are often characterised by inflammatory language targeting the media, which often translates into attacks against journalists. Thus, governments and public officials are reminded that even if political temperatures are high, they have an obligation to prevent, protect and provide justice for journalists.

Governments in Southern Africa are also encouraged to adopt and domesticate the United Nations Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists. This will go a long way in ending impunity and ensuring that there are legal provisions that provide for and promote the safety of journalists.

There is also need for the domestication of the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights (ACHPR) Resolution 522 on the Protection of Women Against Digital Violence in Africa.

Particularly so, the resolutions to undertake measures to safeguard women journalists from digital violence, including gender-sensitive media literacy and digital security training; and to repeal vague and overly wide laws on surveillance as they contribute to the existing vulnerability of female journalists.

MISA Regional Statement on International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists

Golden Maunganidze

MISA Regional Chairperson